Alcohol and Epilepsy

People who use alcohol appear to be more vulnerable to epilepsy. The more they drink, the more likely unprovoked seizures are.

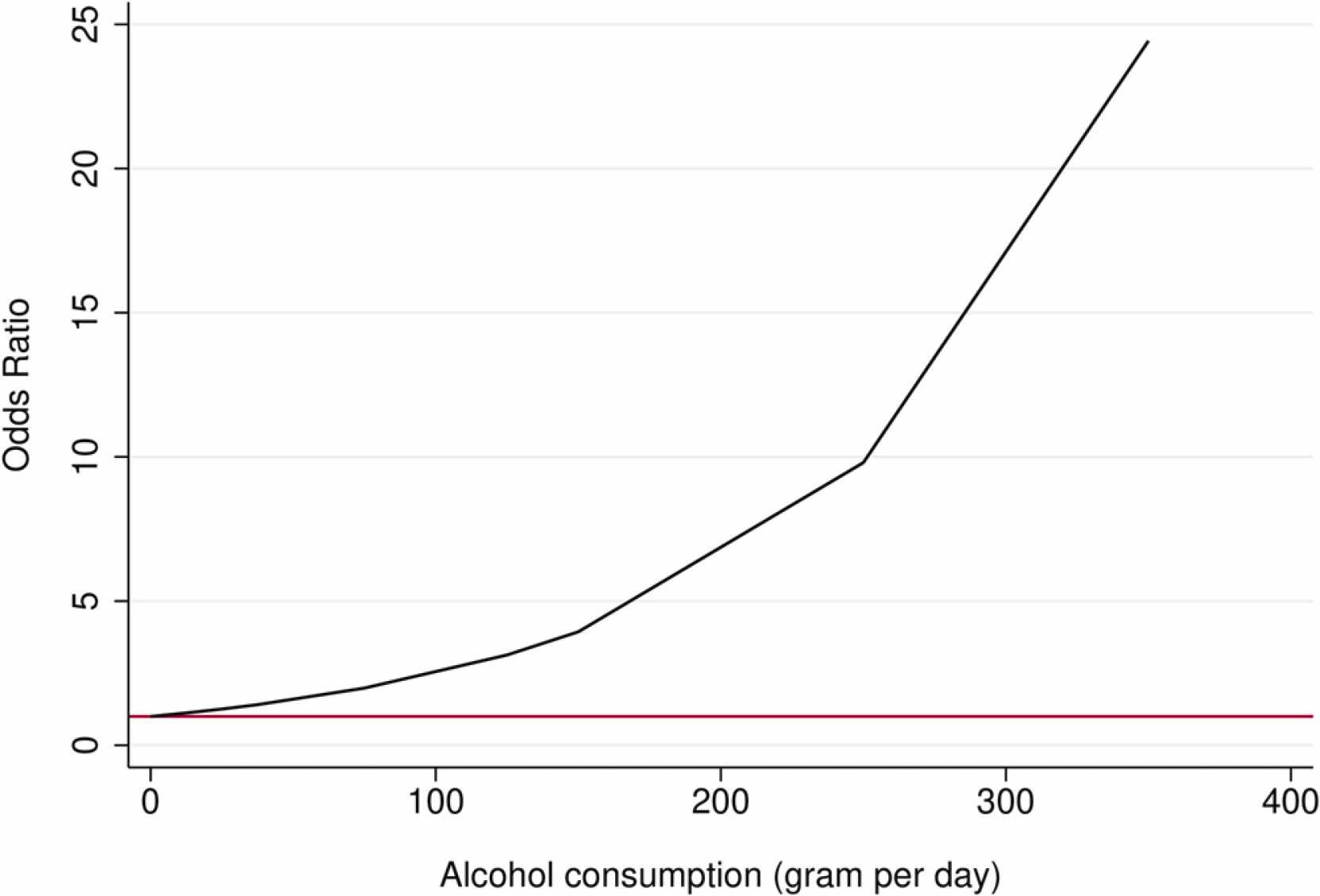

In this meta-analysis Woo et al. 2022 they found the overall odds ratio of developing epilepsy in alcohol users compared to non-drinkers was 1.70 (CI 1.16–2.49). In fact, they found a nonlinear relationship between alcohol consumed and odds ratio (OR) of epilepsy. Look:

In a very recent systematic review, Kwon et al. also found ORs of “alcohol misuse” and “alcohol abuse” to be 3.64 (2.27–5.83) and 2.10 (0.60–7.37), respectively, in people with epilepsy (PWE).

Woo et al. 2022 does provide an important caveat in their discussion: “cohort studies did not show a significant association between alcohol consumption and epilepsy in the subgroup analysis”; “two out of three cohort studies showed that alcohol consumption was associated with a lower risk of epilepsy, although this was not significant” (emphasis mine). An important digressive point is that if the results did not meet their α then the risk can’t be said to be really lower. Nevertheless buried in the discussion they write “Considering these temporal relationships and differences in study design, alcohol may not actually increase the risk of epilepsy, as seen in our subgroup analysis for cohort studies.” What a bomb to drop!

Another paper by Cvetkovska et al. finds structural lesions are the most prevalent risk factor associated with new-onset epilepsy in patients over 50. Which, duh. But it also finds “chronic alcoholism” to be the most common metabolic risk factor accounting for 84% of cases in the subgroup with metabolic risk factors.

Interestingly in this Mendelian randomization study the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) related to alcoholic drinks per week were not associated with an elevated OR of epilepsy. They further point to Leone et al., a case-control study which specifically looked at symptomatic seizures, as a counterpoint to several other studies showing positive findings. Including Samokhvalov et al. 2010, a robust meta-analysis.

Their discussion of alcohol and epilepsy risk is a bit sparse, citing a 1978 study on the kindling effects of alcohol withdrawal (Ballenger & Post 1978) and spuriously citing another study that contravenes its main points. “Our genetic prediction results are in concordance with these observations, indicating that alcoholic drinks per week are not significantly associated with epilepsy risk,” is a bold statement for a paper that uses genetics as a proxy for alcohol exposure.

The kindling paper deserves some attention. They followed a convenience sample of 200 men admitted for inpatient treatment of alcoholism at the National Naval Medical Center. They excluded men with evidence of any brain damage. They didn’t find enough patients with delirium tremens (DT) so they dug for additional patients with that discharge diagnosis in the same index period. The primary finding was that worse withdrawal symptoms were associated with longer years of alcoholism.

They then posit that a “kindling-like process” leads to cumulative physiologic changes that, in turn, lead to a worsening in the spectrum of withdrawal symptoms. They make seven predictions based on this model and then marshal citations to show how each prediction might be plausible.

What especially interests me is the ambiguity of the term kindling. Kindling in one sense refers specifically to the effect of induced seizures, typically by electrical shocks, in causing escalating ictal duration and ictal-behavioral manifestations eventually leading to a plateau that persists even with periods of no stimulation (Bertram 2007). It is important to note this phenomenon has been established in animal models and not definitively in humans.

Kindling is sometimes used as a shorthand to talk about the process of epileptogenesis, especially in the limbic system, although as Bertram 2007 points out this process is somewhat different from the strict sense of kindling in animal models.

In Ballenger & Post we see them refer to kindling as a model for alcohol withdrawal seizures. There is no original data in the paper that suggests that alcohol withdrawal kindles seizures, let alone that it leads to spontaneous seizures.

So that brings us back to the idea that alcohol exposure makes people more liable to developing epilepsy. Even given the caveats of Woo et al. we have additional evidence from Samokhvalov et al. showing a dose-response relationship. The same authors write about several hypotheses: effects from trauma, hypoxia, and kindling. They unfortunately also misinterpret Ballenger & Post about their kindling claims. Samokhvalov et al. also describe neurotransmitter system changes such as dysregulation of GABARs and increased glutamate.

Ultimately it’s not clear what causes epilepsy in people who consume alcohol. It appears that alcohol does increase the risk of epilepsy. Kindling is a term with too much ambiguity in this field.

Remember that alcohol is a poison and is not good for you.